Fashion

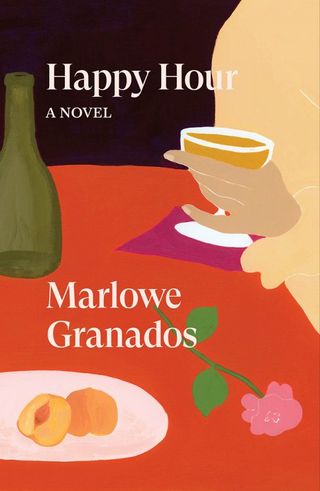

Marlowe Granados Can Get You In Anywhere

Published

3 years agoon

By

Terry Power

How do you make the most out of a summer in New York? Happy Hour is a charming ode to the young women traipsing around downtown who always have somewhere to be. The debut novel by Marlowe Granados, written in diary form, takes place in one electric summer in New York, from late May to Labor Day. The 21-year-old protagonists, Isa and Gala, always seem to be whisked away to parties and art openings at a moment’s notice and sneaking in the back door of places where they wouldn’t otherwise be allowed. Happy Hour is confirmation that it’s possible to meet people and make connections with strangers in passing—if we’re bold enough to follow Isa’s lead.

Granados writes about clothes and style the way that Nora Ephron writes about food. She extends grace and patience to her protagonists, never condescending to the confident young women looking for their next gig to pay this month’s rent. The book might make you nostalgic for your early 20s, the author’s age when she wrote the novel. But as Gala, the headstrong half of the duo, says, “I, for one, am trying to stay young for as long as possible.” There is no time for sadness when you’re bumping into flings and friends left, right, and center.

Taking inspiration from pre-Code cinema—the era before the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code, which censored how sex and violence could be portrayed on screen—the novel is replete with one-liners and the screwball comedy energy of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, in which infidelity takes place off screen. Echoing the opening line of Pride and Prejudice, Isa fills her diary with witticisms about how a proper party girl should move though life, like a conspiratorial, charismatic new acquaintance whispering secrets at a party, beginning the novel with: “My mother always told me that to be a girl one must be especially clever.”

Granados sat down with ELLE.com the day after she attended Balenciaga’s Met Gala after party, when she was still reeling from meeting Charli D’Amelio. She was in town from her native Toronto for the U.S. publication of Happy Hour. We met up at The Public Hotel—they were serving martinis in plastic cups, which she deemed “not correct”— to talk about indulgence, staying curious, and a new narrative for girls who like to have fun.

In your novel, Isa and Gala work as much as they can so they can live a very modest but glamorous life, just enough to pay for the cab home from a party. But as they work from gig to gig to make money, their life doesn’t always feel aspirational. Were you always interested in that world?

Definitely. I think it’s a constant urge. I like getting away with things. I love that they were able to get away with stuff and there’s a sense of mischief. That’s really important and also really integral to reading the book—feeling a sense of glee about getting away with something. I remember being young and, especially when we were underage, getting in somewhere, like getting snuck in or going through the back door somewhere. The sense of being able to have a night that you instigated was really important to me. I wanted to have these girls be very naughty, go around New York, and people being like, “I don’t know what to do with you.”

It’s really funny to me that these are the kind of girls to whom exciting things just happen. They’re getting whisked away at a moment’s notice. There’s a brief Hamptons interlude. But they also have an incredible confidence and sense of agency. Was that something that you intended on writing into the characters?

When I was young, I never felt that I had no power. I understand, I didn’t have any power, structurally, of course, especially as someone who’s non-white and didn’t come from a privileged background. But the sense that you could take the world by the reins, as a young person, as a young woman was important. I’ve just never seen anything like that in the contemporary landscape, and that annoyed me because I lived like that for so long. I needed there to be something for my friends to consume that felt more realistic to how we live.

Basia Wyszynski

Isa and Gala are reminiscent of characters from old Hollywood and pre-Code cinema. They’re young women doing their thing. But in modern literature, it feels like there always has to be some limiting caveat to reel them back in.

There’s a looming presence of some sort, like violence or something catastrophic happening to them. That doesn’t interest me in terms of a plot device. I understand why people would want that, but it’s also forcing growth in a way that I think is actually kind of overwrought. When things happen to me or my friends, I’m not immediately taking that into my life and being like, I’ve learned from this and I’m never gonna do this again, like, ever. It takes so long to actually be like, Oh, I made a mistake. Maybe I’ll do it again a few other times. We think of novels as these very isolated instances of this kind of form. But I actually think we’re much more accustomed now to have plotless narratives like in TV, in a way that’s much more natural to us. We need to speed up this appetite in other mediums because it’s much more realistic to how people live.

In narrative storytelling, there always has to be the “inciting incident” that happens to the character, but in the city, every single day, there’s an inciting incident.

It is interesting when people are like, “There’s no plot.” Every night is a plot! Every night something’s happening when you live like that. It’s so different. When every night is a new adventure, something bad might happen or something incredible might happen. Then you go to sleep, and then you wake up and you’re ready to have this next thing happen. It’s this accumulation of experiences that is more interesting to me.

“I never think about youth in a way that’s slipping through my fingers. I just think it’s a shift in strength.”

There is something special in writing about these girls who occupy spaces, or want to occupy spaces, that they’re not necessarily allowed to be in. They somehow get their way in there. Is that how you wanted to portray them?

It’s the main theme, and it was more important to me, especially as opposed to romantic situations. I wanted it to be very much like an adventure, but in a way that people wouldn’t expect. When we think about young women, we don’t think of adventure-like narrative. There’s been a [dilution] of young women in the city and the glamour of that. I think it’s so odd that we are like, Oh, it’s just another book about young people in New York. I don’t know how we’ve gotten so jaded about this theme. It’s so bizarre to me because I think that there’s still so much space that you can do it in a different way that isn’t expected.

Your main characters are surprisingly self-aware for 21-year-olds who like they should be going out every night to take full advantage of what the city has to offer. I wonder what you think about the importance of indulging in life in the luxurious way that Isa and Gala do in spite of their economic circumstances.

I think people are always like, Oh party girls, what about that is the thing? I think it’s much more about a philosophy of plunging in and going in so many directions. It’s a shame that young women are so self conscious at that age, because that’s the time when you should be making the most and being the naughtiest, worst version of yourself. I think that once you free yourself, it feels so much more relaxing. I don’t think that people should worry that much about little things. To have young women in the novel be very unapologetic about who they are and not second guess themselves, that’s a large part of what I truly believe. In my adult life, I only recently realized that people are not themselves all the time. That’s super stressful. Even when I’m in my worst state, I don’t worry because I’m like, well, I would have done it anyways. It’s just a nice way to move, I guess.

It helps when you’re a fun person!

Right. Some people are terrible, just naturally. So maybe they shouldn’t do that. It was also important to me for there to be warmth [in the novel]. They’re really generous in the way that they see other people. I think it’s really easy for people to be cruel. When I’m texting someone, it’s actually very easy to be cutting and mean. But it’s harder, when I was writing, I had to go against what my natural reaction would be a lot of the time. Isa is very nice and warm. She’s mischievous in her criticism.

Do you think it’s possible to live a charmed or charming life in a bleak world?

I think it has something to do with curiosity and having this childlike way about looking into the world. The whole philosophy of these girls is they’re always saying yes. I think that people should just be more open and talk to people around them. I wanted to embolden people to be a little bit more adventurous just reading the book. You don’t even have to love the things that they love, either. You have to be a little bit curious about beauty and what you find beautiful. So much about your state is surrounding yourself with things that make you happy and joyful and useful.

You mentioned that the world of Happy Hour is inspired by your younger years. Is that a world that you’re still interested in? How has your life philosophy shifted since then?

I think I’m always going to be interested in that world in a way. I don’t pursue it at the same speed anymore. I never think about youth in a way that’s slipping through my fingers. I just think it’s a shift in strength. A lot of times I’ll be in situations when I’m like, thank God I’m older, because I said the thing that when I was younger, I would have been worried to say. I’m now interested in the ways in which you kind of lose a certain type of power. With a lot of my guy friends who date younger women, I’m not suspicious, but I’m also really interested in that shift. How is it that I feel so good being older, and yet age in general as a woman is not good? Youth, in the novel, and being a young girl is a cute trick. It’s a thing people invest money in. I’m more interested now in terms of power and how in getting older you gain a kind of power that you didn’t have before. That’s for the second book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jessica Jacolbe is a writer from Brooklyn whose work appears in VICE, JSTOR Daily, and Catapult.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

You may like

Fashion

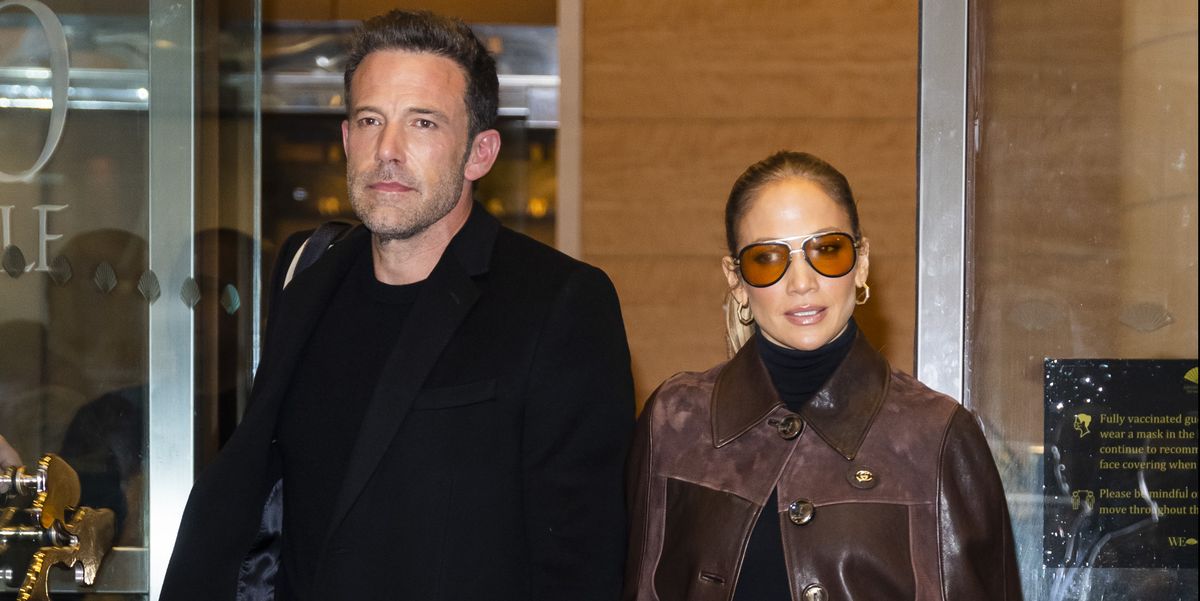

Jennifer Lopez Joined Ben Affleck In L.A. With Kids For Thanksgiving

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

On Wednesday night, Jennifer Lopez arrived in Los Angeles with her 13-year-old twins Max and Emme. The family was likely there to join Lopez’s boyfriend, Ben Affleck, for the Thanksgiving holiday. Lopez recently returned from the much colder climate of British Columbia, Canada, where she was filming her latest project, The Mother.

J. Lo touched down in her private jet wearing a teddy fur coat from Coach’s Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, and a pair of Ugg boots. Classic airplane outfit, celebrity style. Lopez and Affleck originally dated in 2002 and broke up in 2004. Their romance was rekindled earlier this year, soon after Lopez ended her relationship with baseball player Alex Rodriguez. The new couple went official in July, while celebrating Lopez’s 52nd birthday abroad.

Affleck’s most recent relationship with Ana de Armas ended in January after about a year together. He had divorced ex-wife Jennifer Garner in 2015 after being married for almost a decade. Garner and Affleck had three daughters, Violet, Seraphina, and Sam.

Before traveling back to the U.S., Lopez posted a story to Instagram Reels about how grateful she was to be headed home.

“Hey everybody, it’s my last day here shooting on The Mother out in Smithers in the snow, it’s been beautiful, but tonight I’m on my way home,” she said, as she walked through the wild landscape in a black coat and beanie.

“I’m so excited for Thanksgiving! I hope everybody has an amazing weekend with their families and their loved ones, there’s so much to be grateful for this year. I’m on my way!”

This is the first major holiday of the year since Lopez and Affleck reunited, so it’s likely to be a big one for both families.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Fashion

Everlane’s Black Friday Sale is Packed With Winter Essentials

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

Courtesy

This is not a drill: Everlane just kicked off its Black Friday sale. Now through Monday, November 29, the direct-to-consumer brand is offering 20 to 40% off its cozy sweaters, minimalist activewear, and popular jeans. If you’re not super familiar with Everlane, let me spell it out for you: this is a big deal.

The e-tailer might be known for making sustainable, ethically made clothes and accessories at a fair, affordable price, but Everlane rarely has sales beyond its Choose What You Pay section. So, if you want to stock up on cute basics for less, now’s your time to shop.

And, in true Everlane fashion, the brand is taking this opportunity to give back. Everlane is partnering with Rodale Institute and help U.S. farmers transition their farmland to regenerative organic—and donating $15 per order to the cause. A great sale that gives back? I’m sold.

But, hurry! These deals are going to sell out fast, so you won’t want to waste any time filling your e-cart.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

1

The Cloud Turtleneck

$150 $105 (30% off)

Sweater weather is officially here, so why not pick up a few fresh layers? This turtleneck is the S’s: snuggly, stylish, and on sale.

2

The Authentic Stretch High-Rise Skinny Jeans

everlane

$78 $58 (25% off)

Looking for a great pair of jeans, minus the markup? Everlane’s classic skinny style is not only super stretchy, but it’ll look good with everything from chunky sweaters to silky blouses.

3

The ReNew Teddy Slippers

everlane

$65 $39 (40% off)

Why limit the shearling trend to the upper half of your body? These plush slippers will give even your most worn-in sweats a stylish edge.

4

The Chunky Cardigan

everlane

$110 $77 (30% off)

Sure, this may not be the cardigan Taylor Swift was talking about. But, with an exaggerated collar and ribbed finish, this style would definitely score top marks from the singer herself.

5

The Canvas Utility Boots

everlane

$115 $59 (40% off)

Brave the cold weather in style with Everlane’s chic boots. The canvas uppers and thick sole make these an ideal, all-weather option.

6

The Lofty-Knit Henley

everlane

$150 $105 (30% off)

Made with a nubby blend of merino wool, alpaca, and recycled nylon, this henley is perfect for a cozy night in, yet stylish enough to wear in public.

7

The Perform Bike Shorts

everlane

$45 $22 (51% off)

No, you can never have too many stretchy pants. Everlane’s bike shorts ooze major Lady Di vibes — for under $25, no less.

8

The ReLeather Court Sneakers

everlane

$110 $66 (40% off)

Made with recycled leather, these refresh sneakers will serve up major curb appeal — and Mother Nature’s seal of approval.

9

The Field Dress

everlane

$100 $60 (40% off)

Found: a fun, flouncy frock you can wear year-round. For a wintry take, pair with opaque tights and your favorite chunky boots.

10

The Cozy-Stretch Wide-Leg Sweatpants

everlane

$150 $75 (50% off)

With a straight-legged silhouette and wool material, it’s safe to say these are the chicest sweatpants we’ve ever seen. To sweeten an already enticing offer, this pair is half off.

11

The Organic Cotton Flannel Popover

$80 $56 (30% off)

Everlane reimagined the traditional flannel with a cropped silhouette, voluminous sleeves, and a slew of minimalist colors.

12

The Studio Bag

everlane

$275 $192 (30% off)

Large enough to fit all your essentials, but not too big that it’ll weigh you down, Everlane’s Studio Bag is the perfect everyday purse.

13

The ReNew Long Liner

everlane

$158 $118 (25% off)

House Stark was right: winter really is coming. Made with recycled materials, this liner is a great layering piece that’s considerably chicer than the yesteryear’s Michelin Man-worthy parkas.

14

The Felted Merino Beanie

everlane

$50 $30 (40% off)

All set on clothes? Pick up this cheery beanie, which is 40% off its original price.

Kelsey Mulvey is a freelance lifestyle journalist, who covers shopping and deals for Marie Claire, Women’s Health, and Men’s Health, among others.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Fashion

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy