Fashion

She’s Running the New York City Marathon for All Afghan Women Who Can’t

Published

4 years agoon

By

Terry Power

In August, the world watched in horror as the Taliban swiftly overtook Afghanistan’s capital of Kabul following the withdrawal of U.S. troops, ending a 20-year-long occupation. Articles depicted brutal, inhumane acts of violence; photos surfaced of Afghan civilians swarming the airport, desperate to flee Taliban rule. But few were more surprised than Zahra*, a 29-year-old Afghan scholar and soon-to-be marathon runner, who had said goodbye to her home, her friends, and her family in Afghanistan just five days earlier to pursue her master’s degree in finance at a university in New Hampshire.

“I never thought that the Taliban would take Kabul that soon,” she says. “It was shocking. When they first came to Afghanistan, I was a child. Now, as an Afghan woman in the U.S., I don’t feel the distress that Afghan women are currently going through in Afghanistan.” She pauses to let out a sigh, weighed heavy by grief. “I’m very fortunate, but I feel guilty, too.”

Zahra was 4 years old when she experienced her first brush with the Taliban. It was 1996, the year that the Islamic extremist group first rose to power and established what would go on to become a five-year-long regime. She remembers the moment—a searing memory that would shape the trajectory of her life—with incredible clarity: the motorcycles on which they rode in on (to this day, the revving of motorcycles still fills her with terror), her father, standing in a soccer field, being captured and taken away as she watched helplessly from afar. She rushed home to tell her mother and uncles what had happened. Their reaction was one of complete and utter disbelief, and they were left with only one question: What do we do now? Raise money. The Taliban wanted money.

“We sold everything to release my father—everything we had, we sold. We wanted our father back,” says Zahra, who explains that as Hazaras, a minority ethnic group living in the Dasht-e-Barchi area of Kabul, they have long faced persecution. “When my father was released after three months, his body was covered in injuries from the beatings—from the torture. He lost his legs because of it, and now, my father cannot walk properly.”

After his release, her father was adamant that they leave the country altogether. So the entire family—Zahra, her mother and father, and her two older brothers—crammed into a car and they drove for two days straight until they reached Pakistan, where they started life completely from scratch. It was here that Zahra, at age 4, and her two brothers (ages 6 and 8) spent their days, from morning to night, weaving rugs to help earn money for the family. When she turned 6, she started going to school during lunchtime. In those two hours, in a classroom with 20 other students of all ages, she learned math (her favorite subject) and English.

“I knew from a young age that the Taliban didn’t allow girls to have an education and I didn’t understand—why not?” she says. “There was a desire in my heart to learn. My parents never told me I shouldn’t study, but I felt like they supported my brothers more than me.” She stops to laugh before continuing: “I wanted to prove to them I was more capable than my brothers, so I studied harder than them. I studied even when I was weaving. Whenever I had free time, I was writing, reading, or doing homework.”

Zahra’s family returned to Afghanistan in 2001, after the U.S. toppled the Taliban regime post-9/11. At 9 years old, Zahra was finally home again. It was a bittersweet moment—she was happy to be reunited with her extended family, but she was crushed to see the destruction that the war ravaged on her homeland. “Everything was damaged,” she remembers. “So again, we started from zero and had to build our home back.”

She calls the 20-year-long U.S. occupation a golden time. The era of opportunity. Women had choices: they could wear whatever they wanted (a hijab, for example, like the one she currently wears, versus a burka), they could work, they could run businesses, they could pursue an education, they could engage in sports. Though to be clear, she’s talking about the more progressive provinces in Afghanistan, which include Kabul, Bamiyan, and Herat; other areas were still very conservative. Zahra took full advantage of the opportunity and became a full-time student, throwing herself into her studies, which earned her top marks and access to certain classes, like computers and English (by the time she graduated high school, she was teaching computer courses to other women). In order to continue onto higher education, Afghan students are required to take the Kankor exam, a university entrance test administered by the Ministry of Higher Education of Afghanistan. Zahra earned a score of 316 out of 360, making her the highest-scoring student in her school.

Michael ReavesGetty Images

“The women in Afghanistan are the main source of my inspiration. I keep praying for them, and it is for them that I run.”

“My headmaster told me, ‘You are the pride of our school,’” says Zahra, who earned a degree in economics and later landed a job as a finance specialist. “My mother, father, and brothers were all really proud. Entering Kabul University is very hard, because you need to have a high score to be accepted.”

Another big moment was learning how to ride a bike. Zahra had always been interested in sports—cycling especially, after seeing boys ride their bikes. So why not her? “My mother told me that a woman cannot cycle, that it’s bad—because it’s sexy,” she giggles. “It’s funny, but at the same time, it made me mad. I told her I was going to learn. I was aware then that women can do anything, and I wanted to ride a bicycle.”

In 2016, when she was 24, Zahra dedicated a couple of months learning to achieve what she thought was an impossible task at her age. She was convinced that it was something only children could pick up, but she practiced every day in her home, with her hand on the wall to steady her balance (she fell twice, and on one occasion, she broke her hand), and eventually mastered it. Two years later, she joined the BorderFree Cycling, and soon after, Freeto Run, a program that empowers women and girls in conflict-affected regions to participate in sports, where she was able to run with other girls. And in 2019, she became involved with SheCan Tri, which gave her the opportunity to race in triathlons.

But it’s the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other that has been the most liberating. Zahra first started running in 2018 at a time in her life when she was deeply unhappy at her job and working with an unsupportive supervisor. She discovered that it allowed her to feel free. “When I woke up in the morning to run, it motivated me to bear those distresses I had in my job,” she says. “It was a kind of therapy for me.”

And running continues to serve as something like therapy for her. Now, alone in the U.S. (the result of receiving the Fulbright scholarship), thousands of miles away from her family, learning about the near-daily explosions in Afghanistan and feeling utterly powerless to help, she copes by running—and on Nov. 7, she’ll be running in the 50th TCS New York City Marathon on behalf of Free to Run, one of the marathon’s 490 charity partners.

“Whenever I feel like I can’t run any further, I think about all the girls and women who cannot run in Afghanistan, who cannot get an education, who cannot go to work—their problems are bigger than me, and when I remember them, it motivates me to keep going, to do whatever I can for Afghan women and my family,” she says, resolutely. “The women in Afghanistan are the main source of my inspiration. I keep praying for them, and it is for them that I run.”

Zahra recounts a conversation she had with a friend recently, a woman back home in Afghanistan who says that the Taliban have banned everything for women, taking away their dreams, their hopes, and their lives. In other words, “the meaning of life,” she says, “is broken.”

She’s all too aware that her existence—her hard-earned scholarship, her connections with charity programs and athletic clubs—puts her family’s lives in immediate danger. Anyone linked to the U.S. is considered a threat, and if the Taliban discovered her and her family, they would torture them. Still, she’s doing her best to drum up noise, to do anything she can to help her family escape. If there’s one thing she wants the world to know, it’s that Afghan women are capable of anything—they can be engineers, doctors, pilots, runners. She offers herself as an example: “I’m in the U.S. getting my masters, and I’m about to run a marathon. All Afghan people are like me; all Afghan women are even more capable than me. I don’t want the world to forget about Afghan women.”

*Zahra’s last name and key details have been withheld to protect her identity and ensure the safety of her family in Afghanistan.

Andrea Cheng is a New York-based writer who writes about fashion and beauty.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

You may like

-

The $100 billion bet that a postindustrial US city can reinvent itself as a high-tech hub

-

20% Of Women Who Need Fertility Treatment Can Get Pregnant Naturally Later: Study

-

The US city that scares Chinese Amazon sellers

-

Overdose Deaths: Men In The US At Higher Risk Than Women, Says Study

-

Healthy Perivascular Fat May Protect Against Dementia In Postmenopausal Women: Study

-

New York Hospitals Want To Rehire Employees Fired Over Vaccine Mandate

Fashion

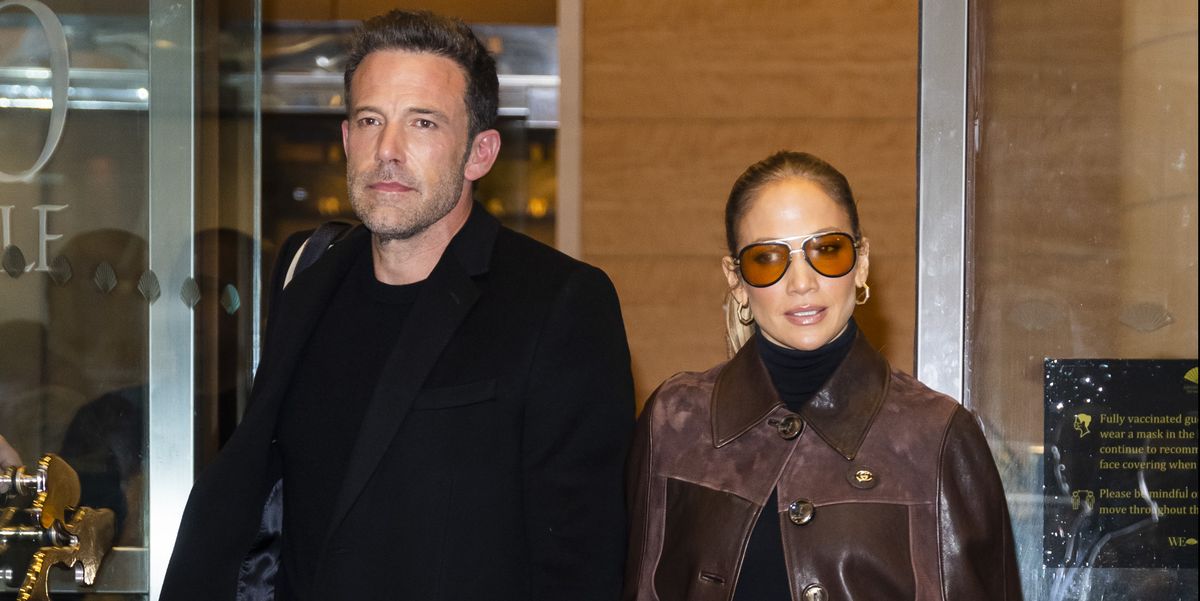

Jennifer Lopez Joined Ben Affleck In L.A. With Kids For Thanksgiving

Published

4 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

On Wednesday night, Jennifer Lopez arrived in Los Angeles with her 13-year-old twins Max and Emme. The family was likely there to join Lopez’s boyfriend, Ben Affleck, for the Thanksgiving holiday. Lopez recently returned from the much colder climate of British Columbia, Canada, where she was filming her latest project, The Mother.

J. Lo touched down in her private jet wearing a teddy fur coat from Coach’s Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, and a pair of Ugg boots. Classic airplane outfit, celebrity style. Lopez and Affleck originally dated in 2002 and broke up in 2004. Their romance was rekindled earlier this year, soon after Lopez ended her relationship with baseball player Alex Rodriguez. The new couple went official in July, while celebrating Lopez’s 52nd birthday abroad.

Affleck’s most recent relationship with Ana de Armas ended in January after about a year together. He had divorced ex-wife Jennifer Garner in 2015 after being married for almost a decade. Garner and Affleck had three daughters, Violet, Seraphina, and Sam.

Before traveling back to the U.S., Lopez posted a story to Instagram Reels about how grateful she was to be headed home.

“Hey everybody, it’s my last day here shooting on The Mother out in Smithers in the snow, it’s been beautiful, but tonight I’m on my way home,” she said, as she walked through the wild landscape in a black coat and beanie.

“I’m so excited for Thanksgiving! I hope everybody has an amazing weekend with their families and their loved ones, there’s so much to be grateful for this year. I’m on my way!”

This is the first major holiday of the year since Lopez and Affleck reunited, so it’s likely to be a big one for both families.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Fashion

Everlane’s Black Friday Sale is Packed With Winter Essentials

Published

4 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

Courtesy

This is not a drill: Everlane just kicked off its Black Friday sale. Now through Monday, November 29, the direct-to-consumer brand is offering 20 to 40% off its cozy sweaters, minimalist activewear, and popular jeans. If you’re not super familiar with Everlane, let me spell it out for you: this is a big deal.

The e-tailer might be known for making sustainable, ethically made clothes and accessories at a fair, affordable price, but Everlane rarely has sales beyond its Choose What You Pay section. So, if you want to stock up on cute basics for less, now’s your time to shop.

And, in true Everlane fashion, the brand is taking this opportunity to give back. Everlane is partnering with Rodale Institute and help U.S. farmers transition their farmland to regenerative organic—and donating $15 per order to the cause. A great sale that gives back? I’m sold.

But, hurry! These deals are going to sell out fast, so you won’t want to waste any time filling your e-cart.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

1

The Cloud Turtleneck

$150 $105 (30% off)

Sweater weather is officially here, so why not pick up a few fresh layers? This turtleneck is the S’s: snuggly, stylish, and on sale.

2

The Authentic Stretch High-Rise Skinny Jeans

everlane

$78 $58 (25% off)

Looking for a great pair of jeans, minus the markup? Everlane’s classic skinny style is not only super stretchy, but it’ll look good with everything from chunky sweaters to silky blouses.

3

The ReNew Teddy Slippers

everlane

$65 $39 (40% off)

Why limit the shearling trend to the upper half of your body? These plush slippers will give even your most worn-in sweats a stylish edge.

4

The Chunky Cardigan

everlane

$110 $77 (30% off)

Sure, this may not be the cardigan Taylor Swift was talking about. But, with an exaggerated collar and ribbed finish, this style would definitely score top marks from the singer herself.

5

The Canvas Utility Boots

everlane

$115 $59 (40% off)

Brave the cold weather in style with Everlane’s chic boots. The canvas uppers and thick sole make these an ideal, all-weather option.

6

The Lofty-Knit Henley

everlane

$150 $105 (30% off)

Made with a nubby blend of merino wool, alpaca, and recycled nylon, this henley is perfect for a cozy night in, yet stylish enough to wear in public.

7

The Perform Bike Shorts

everlane

$45 $22 (51% off)

No, you can never have too many stretchy pants. Everlane’s bike shorts ooze major Lady Di vibes — for under $25, no less.

8

The ReLeather Court Sneakers

everlane

$110 $66 (40% off)

Made with recycled leather, these refresh sneakers will serve up major curb appeal — and Mother Nature’s seal of approval.

9

The Field Dress

everlane

$100 $60 (40% off)

Found: a fun, flouncy frock you can wear year-round. For a wintry take, pair with opaque tights and your favorite chunky boots.

10

The Cozy-Stretch Wide-Leg Sweatpants

everlane

$150 $75 (50% off)

With a straight-legged silhouette and wool material, it’s safe to say these are the chicest sweatpants we’ve ever seen. To sweeten an already enticing offer, this pair is half off.

11

The Organic Cotton Flannel Popover

$80 $56 (30% off)

Everlane reimagined the traditional flannel with a cropped silhouette, voluminous sleeves, and a slew of minimalist colors.

12

The Studio Bag

everlane

$275 $192 (30% off)

Large enough to fit all your essentials, but not too big that it’ll weigh you down, Everlane’s Studio Bag is the perfect everyday purse.

13

The ReNew Long Liner

everlane

$158 $118 (25% off)

House Stark was right: winter really is coming. Made with recycled materials, this liner is a great layering piece that’s considerably chicer than the yesteryear’s Michelin Man-worthy parkas.

14

The Felted Merino Beanie

everlane

$50 $30 (40% off)

All set on clothes? Pick up this cheery beanie, which is 40% off its original price.

Kelsey Mulvey is a freelance lifestyle journalist, who covers shopping and deals for Marie Claire, Women’s Health, and Men’s Health, among others.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Fashion

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy

Published

4 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy