Tech

Why I’m a proud solutionist

Published

4 years agoon

By

Terry Power

Debates about technology and progress are often framed in terms of “optimism” vs. “pessimism.” For instance, Steven Pinker, Matt Ridley, Johan Norberg, Max Roser, and the late Hans Rosling have been called the “New Optimists” for their focus on the economic, scientific, and social progress of the last two centuries. Their opponents, such as David Runciman and Jason Hickel, accuse them of being blind to real problems in the world, such as poverty, and to risks of catastrophe, such as nuclear war.

Economic historian Robert Gordon calls himself “the prophet of pessimism.” His book The Rise and Fall of American Growth warned that the days of high economic growth are over for the United States and will not return. Gordon’s opponents include a group he calls the “techno-optimists,” such as Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, who have predicted a growth spurt in productivity from information technology.

It’s tempting to choose sides. But while it can be rational to be optimistic or pessimistic on any specific question, these terms are too imprecise to be adopted as a general intellectual identity. Those who identify as optimists can be too quick to dismiss or downplay the problems of technology, while self-styled technology pessimists or progress skeptics can be too reluctant to believe in solutions.

As we look forward to the post-pandemic recovery, once again we’re being tugged between the optimists, who highlight all the diseases that may soon be beaten through new vaccines, and the pessimists, who warn that humanity will never win the evolutionary arms race against microbes. But this represents a false choice. History provides us with powerful examples of people who were brutally honest in identifying a crisis but were equally active in seeking solutions.

At the end of the 19th century, William Crookes—physicist, chemist, and inventor of the Crookes tube (an early type of vacuum tube)—was the president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. On September 7, 1898, he used the traditional annual address to the association to issue a dire warning.

The British Isles, he said, were at grave risk of running out of food. His reasoning was simple: the population was growing exponentially, but the amount of land under cultivation could not keep pace. The only way to continue to increase production was to improve crop yields. But the limiting factor on yields was the availability of nitrogen fertilizer, and the sources of nitrogen, such as the rock salts of the Chilean desert and the guano deposits of the Peruvian islands, were running out. His argument was detailed and comprehensive, based on figures for wheat production and land availability from every major European country and colony; he apologized in advance for boring his audience with statistics.

He criticized the “culpably extravagant” waste of nonrenewable nitrogen resources. To those who looked myopically only at recent years of the harvest, which had been quite sufficient, he pointed out that those years had been unusually fruitful, which masked the problem. The bounty of the recent past was no guarantee of prosperity in the future.

In a sense, Crookes was an “alarmist.” His purpose was to draw attention to a problem caused by progress and growth. He sought to open the eyes of the complacent. He began by saying that “England and all civilized nations stand in deadly peril,” variously referring to “a colossal problem” of “urgent importance,” an “impending catastrophe,” and “a life-and-death question for generations to come.” To those who would call him alarmist, he insisted that his message was “founded on stubborn facts.”

Crookes caused a sensation, and many critics spoke against his message. They pointed out that wheat wasn’t the only food, that people would moderate consumption of it if necessary, and that land for wheat could be taken from what was used for meat and dairy production, especially as prices rose. They said that he underestimated the opportunities for American farmers to supply food to other nations, by better adapting their methods to the soil and climate so as to increase production.

Writing in Nature in 1899, one R. Giffen compared Crookes to Thomas Malthus, and to others who had predicted shortages of various natural resources—such as Eduard Suess, who had said that gold would run out, and William Stanley Jevons, who warned about Peak Coal. Giffen’s tone is weary as he notes that “there has been much experience of these discussions since the time of Malthus.” Every time, he explains, we’ve been unable to make precise forecasts because the anticipated limits to growth are too far in the future, or we know too little about their causes.

But Crookes had always intended his remarks to take “the form of a warning rather than of a prophecy.” In the speech, he said:

“It is the chemist who must come to the rescue … Before we are in the grip of actual dearth the chemist will step in and postpone the day of famine to so distant a period that we and our sons and grandsons may legitimately live without undue solicitude for the future.”

Crookes’s plan was to tap a virtually unlimited source of nitrogen: the atmosphere. Plants can’t use atmospheric nitrogen directly; instead, they use other nitrogen-containing compounds, which in nature are manufactured from atmospheric nitrogen by certain bacteria, a process called fixation. Crookes said that the artificial fixation of atmospheric nitrogen was “one of the great discoveries awaiting the ingenuity of chemists,” and he was optimistic that it could happen soon, calling it “a question of the not-far-distant future.”

He devoted a significant part of his speech to exploring this solution. He pointed out that nitrogen can be burned at sufficiently high temperatures to create nitrate compounds, and that this can be done using electricity. He even estimated practical details, such as the cost of the nitrates produced this way, which was competitive at market rates, and whether the process could be scaled up to industrial levels: the new hydroelectric plant at Niagara Falls, he concluded, would alone provide all the electricity needed to make up the gap he had forecast.

Crookes knew that synthetic fertilizer wasn’t a permanent solution, but he was satisfied that when the problem reappeared in the distant future, his successors would be able to deal with it. His alarmism was not a philosophical position, but a contingent one. Once the facts of the situation were changed by the invention of suitable technology, he was happy to call off the alarm.

Was Crookes correct? By 1931, the year he had said we could run out of food, it was clear that his predictions had not been perfect. The harvest had increased, but not because crop yields greatly improved. Instead, acreage had actually increased, to a degree Crookes had thought impossible. This happened in part because of improvements in mechanization, including the gas tractor. Mechanization drove down labor costs, which made marginally yielding lands profitable. As often happens, a solution came from an unexpected direction, invalidating the assumptions of forecasters both optimistic and pessimistic.

But if Crookes was not correct in his detailed predictions, he was correct in essence. His two key points were accurate: one, that food in general and yields in particular were problems that would have to be reckoned with in the next generation or so; two, that synthetic fertilizer from the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen would be a key aspect of the solution.

Less than two decades after his speech, the German chemist Fritz Haber and industrialist Carl Bosch developed a process to synthesize ammonia out of atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen gas. Ammonia is a chemical precursor of synthetic fertilizers, and the Haber-Bosch process is still one of the most important industrial processes today, providing fertilizer for almost half the world’s food production.

The chemist, ultimately, did come to the rescue.

So was Crookes an optimist or a pessimist? He was pessimistic about the problem—he was not complacent. But he was optimistic about finding a solution—he was no defeatist, either.

In the 20th century, fears of overpopulation and food supply once again reared their heads. In 1965, the world population growth rate reached an all-time high of 2% per year, enough to double every 35 years; and as late as 1970, it is estimated, over a third of people in developing countries were undernourished.

The 1968 book The Population Bomb, by Paul and Anne Ehrlich, opened with a call for surrender: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” In 1970, Paul Ehrlich reinforced the defeatism, saying that in a few years “further efforts will be futile” and “you may as well look after yourself and your friends and enjoy what little time you have left.” Because they saw the situation as hopeless, the Ehrlichs supported a proposal to cut off aid to countries such as India that were seen as not doing enough to limit population growth.

Fortunately for India and the rest of the world, others were not ready to give up. Norman Borlaug, working in Mexico in a program funded by the Rockefeller Institute, developed high-yield varieties of wheat that resisted fungal disease, used fertilizer more efficiently, and could grow at any latitude. In the 1960s, thanks in part to the new grains, Mexico transformed itself from an importer to an exporter of wheat and India and Pakistan nearly doubled their yields, averting the famine that the Ehrlichs saw as inevitable.

Yet even after winning the Nobel Peace Prize for his accomplishments, Borlaug never lost sight of the challenge involved in making agriculture keep up with population, and never considered it solved for good. In his 1970 Nobel lecture, he called the increases in food production “still modest in terms of total needs” and, pointing out that half the world is undernourished, said “no room is left for complacency.” He warned that “most people still fail to comprehend the magnitude and menace of the ‘Population Monster.’” “And yet,” he continued, “I am optimistic for the future of mankind.” Borlaug was confident that human reason would eventually bring population under control (and indeed, the global birth rate has been declining ever since).

The risk of adopting an “optimistic” or “pessimistic” mindset is the temptation to take sides on an issue depending on a general mood, rather than forming an opinion based on the facts of the case. “Don’t worry,” says the optimist; “accept hardship,” counters the pessimist.

We should be fundamentally neither optimists nor pessimists, but solutionists.

We can see this play out in debates over covid and lockdowns, over climate change and energy usage, over the promise and peril of nuclear power, and in general over economic growth and resource consumption. As the debates escalate, each side digs in: the “optimists” question whether a threat is even real; the “pessimists” deride any proposed technological solution as a false “quick fix” that merely allows us to rationalize postponing the difficult but inevitable cutbacks. (For an example of the latter, see the “moral hazard” arguments against geoengineering as a strategy to address climate change.)

To embrace both the reality of problems and the possibility of overcoming them, we should be fundamentally neither optimists nor pessimists, but solutionists.

The term “solutionism,” usually in the form of “technocratic solutionism,” has been used since the 1960s to mean the belief that every problem can be fixed with technology. This is wrong, and so “solutionism” has been a term of derision. But if we discard any assumptions about the form that solutions must take, we can reclaim it to mean simply the belief that problems are real, but solvable.

Solutionists may seem like optimists because solutionism is fundamentally positive. It advocates vigorously advancing against problems, neither retreating nor surrendering. But it is as far from a Panglossian, “all is for the best” optimism as it is from a fatalistic, doomsday pessimism. It is a third way that avoids both complacency and defeatism, and we should wear the term with pride.

Jason Crawford is the author of The Roots of Progress, a website about the history of technology and industry.

You may like

-

How a half-trillion dollars is transforming climate technology

-

Next slide, please: A brief history of the corporate presentation

-

Human-plus-AI solutions mitigate security threats

-

Introducing MIT Technology Review Roundtables, real-time conversations about what’s next in tech

-

The forgotten history of highway photologs

-

Feeling Tired All The Time? Possible Causes And Solutions

My senior spring in high school, I decided to defer my MIT enrollment by a year. I had always planned to take a gap year, but after receiving the silver tube in the mail and seeing all my college-bound friends plan out their classes and dorm decor, I got cold feet. Every time I mentioned my plans, I was met with questions like “But what about school?” and “MIT is cool with this?”

Yeah. MIT totally is. Postponing your MIT start date is as simple as clicking a checkbox.

COURTESY PHOTO

Now, having finished my first year of classes, I’m really grateful that I stuck with my decision to delay MIT, as I realized that having a full year of unstructured time is a gift. I could let my creative juices run. Pick up hobbies for fun. Do cool things like work at an AI startup and teach myself how to create latte art. My favorite part of the year, however, was backpacking across Europe. I traveled through Austria, Slovakia, Russia, Spain, France, the UK, Greece, Italy, Germany, Poland, Romania, and Hungary.

Moreover, despite my fear that I’d be losing a valuable year, traveling turned out to be the most productive thing I could have done with my time. I got to explore different cultures, meet new people from all over the world, and gain unique perspectives that I couldn’t have gotten otherwise. My travels throughout Europe allowed me to leave my comfort zone and expand my understanding of the greater human experience.

“In Iceland there’s less focus on hustle culture, and this relaxed approach to work-life balance ends up fostering creativity. This was a wild revelation to a bunch of MIT students.”

When I became a full-time student last fall, I realized that StartLabs, the premier undergraduate entrepreneurship club on campus, gives MIT undergrads a similar opportunity to expand their horizons and experience new things. I immediately signed up. At StartLabs, we host fireside chats and ideathons throughout the year. But our flagship event is our annual TechTrek over spring break. In previous years, StartLabs has gone on TechTrek trips to Germany, Switzerland, and Israel. On these fully funded trips, StartLabs members have visited and collaborated with industry leaders, incubators, startups, and academic institutions. They take these treks both to connect with the global startup sphere and to build closer relationships within the club itself.

Most important, however, the process of organizing the TechTrek is itself an expedited introduction to entrepreneurship. The trip is entirely planned by StartLabs members; we figure out travel logistics, find sponsors, and then discover ways to optimize our funding.

COURTESY PHOTO

In organizing this year’s trip to Iceland, we had to learn how to delegate roles to all the planners and how to maintain morale when making this trip a reality seemed to be an impossible task. We woke up extra early to take 6 a.m. calls with Icelandic founders and sponsors. We came up with options for different levels of sponsorship, used pattern recognition to deduce the email addresses of hundreds of potential contacts at organizations we wanted to visit, and all got scrappy with utilizing our LinkedIn connections.

And as any good entrepreneur must, we had to learn how to be lean and maximize our resources. To stretch our food budget, we planned all our incubator and company visits around lunchtime in hopes of getting fed, played human Tetris as we fit 16 people into a six-person Airbnb, and emailed grocery stores to get their nearly expired foods for a discount. We even made a deal with the local bus company to give us free tickets in exchange for a story post on our Instagram account.

Tech

The Download: spying keyboard software, and why boring AI is best

Published

2 years agoon

22 August 2023By

Terry Power

This is today’s edition of The Download, our weekday newsletter that provides a daily dose of what’s going on in the world of technology.

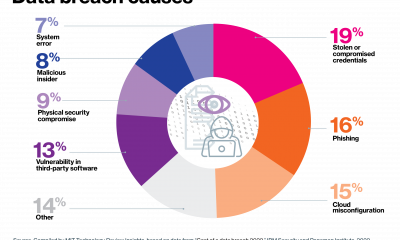

How ubiquitous keyboard software puts hundreds of millions of Chinese users at risk

For millions of Chinese people, the first software they download onto devices is always the same: a keyboard app. Yet few of them are aware that it may make everything they type vulnerable to spying eyes.

QWERTY keyboards are inefficient as many Chinese characters share the same latinized spelling. As a result, many switch to smart, localized keyboard apps to save time and frustration. Today, over 800 million Chinese people use third-party keyboard apps on their PCs, laptops, and mobile phones.

But a recent report by the Citizen Lab, a University of Toronto–affiliated research group, revealed that Sogou, one of the most popular Chinese keyboard apps, had a massive security loophole. Read the full story.

—Zeyi Yang

Why we should all be rooting for boring AI

Earlier this month, the US Department of Defense announced it is setting up a Generative AI Task Force, aimed at “analyzing and integrating” AI tools such as large language models across the department. It hopes they could improve intelligence and operational planning.

But those might not be the right use cases, writes our senior AI reporter Melissa Heikkila. Generative AI tools, such as language models, are glitchy and unpredictable, and they make things up. They also have massive security vulnerabilities, privacy problems, and deeply ingrained biases.

Applying these technologies in high-stakes settings could lead to deadly accidents where it’s unclear who or what should be held responsible, or even why the problem occurred. The DoD’s best bet is to apply generative AI to more mundane things like Excel, email, or word processing. Read the full story.

This story is from The Algorithm, Melissa’s weekly newsletter giving you the inside track on all things AI. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Monday.

The ice cores that will let us look 1.5 million years into the past

To better understand the role atmospheric carbon dioxide plays in Earth’s climate cycles, scientists have long turned to ice cores drilled in Antarctica, where snow layers accumulate and compact over hundreds of thousands of years, trapping samples of ancient air in a lattice of bubbles that serve as tiny time capsules.

By analyzing those cores, scientists can connect greenhouse-gas concentrations with temperatures going back 800,000 years. Now, a new European-led initiative hopes to eventually retrieve the oldest core yet, dating back 1.5 million years. But that impressive feat is still only the first step. Once they’ve done that, they’ll have to figure out how they’re going to extract the air from the ice. Read the full story.

—Christian Elliott

This story is from the latest edition of our print magazine, set to go live tomorrow. Subscribe today for as low as $8/month to ensure you receive full access to the new Ethics issue and in-depth stories on experimental drugs, AI assisted warfare, microfinance, and more.

The must-reads

I’ve combed the internet to find you today’s most fun/important/scary/fascinating stories about technology.

1 How AI got dragged into the culture wars

Fears about ‘woke’ AI fundamentally misunderstand how it works. Yet they’re gaining traction. (The Guardian)

+ Why it’s impossible to build an unbiased AI language model. (MIT Technology Review)

2 Researchers are racing to understand a new coronavirus variant

It’s unlikely to be cause for concern, but it shows this virus still has plenty of tricks up its sleeve. (Nature)

+ Covid hasn’t entirely gone away—here’s where we stand. (MIT Technology Review)

+ Why we can’t afford to stop monitoring it. (Ars Technica)

3 How Hilary became such a monster storm

Much of it is down to unusually hot sea surface temperatures. (Wired $)

+ The era of simultaneous climate disasters is here to stay. (Axios)

+ People are donning cooling vests so they can work through the heat. (Wired $)

4 Brain privacy is set to become important

Scientists are getting better at decoding our brain data. It’s surely only a matter of time before others want a peek. (The Atlantic $)

+ How your brain data could be used against you. (MIT Technology Review)

5 How Nvidia built such a big competitive advantage in AI chips

Today it accounts for 70% of all AI chip sales—and an even greater share for training generative models. (NYT $)

+ The chips it’s selling to China are less effective due to US export controls. (Ars Technica)

+ These simple design rules could turn the chip industry on its head. (MIT Technology Review)

6 Inside the complex world of dissociative identity disorder on TikTok

Reducing stigma is great, but doctors fear people are self-diagnosing or even imitating the disorder. (The Verge)

7 What TikTok might have to give up to keep operating in the US

This shows just how hollow the authorities’ purported data-collection concerns really are. (Forbes)

8 Soldiers in Ukraine are playing World of Tanks on their phones

It’s eerily similar to the war they are themselves fighting, but they say it helps them to dissociate from the horror. (NYT $)

9 Conspiracy theorists are sharing mad ideas on what causes wildfires

But it’s all just a convoluted way to try to avoid having to tackle climate change. (Slate $)

10 Christie’s accidentally leaked the location of tons of valuable art

Seemingly thanks to the metadata that often automatically attaches to smartphone photos. (WP $)

Quote of the day

“Is it going to take people dying for something to move forward?”

—An anonymous air traffic controller warns that staffing shortages in their industry, plus other factors, are starting to threaten passenger safety, the New York Times reports.

The big story

Inside effective altruism, where the far future counts a lot more than the present

October 2022

Since its birth in the late 2000s, effective altruism has aimed to answer the question “How can those with means have the most impact on the world in a quantifiable way?”—and supplied methods for calculating the answer.

It’s no surprise that effective altruisms’ ideas have long faced criticism for reflecting white Western saviorism, alongside an avoidance of structural problems in favor of abstract math. And as believers pour even greater amounts of money into the movement’s increasingly sci-fi ideals, such charges are only intensifying. Read the full story.

—Rebecca Ackermann

We can still have nice things

A place for comfort, fun and distraction in these weird times. (Got any ideas? Drop me a line or tweet ’em at me.)

+ Watch Andrew Scott’s electrifying reading of the 1965 commencement address ‘Choose One of Five’ by Edith Sampson.

+ Here’s how Metallica makes sure its live performances ROCK. ($)

+ Cannot deal with this utterly ludicrous wooden vehicle.

+ Learn about a weird and wonderful new instrument called a harpejji.

Tech

Why we should all be rooting for boring AI

Published

2 years agoon

22 August 2023By

Terry Power

This story originally appeared in The Algorithm, our weekly newsletter on AI. To get stories like this in your inbox first, sign up here.

I’m back from a wholesome week off picking blueberries in a forest. So this story we published last week about the messy ethics of AI in warfare is just the antidote, bringing my blood pressure right back up again.

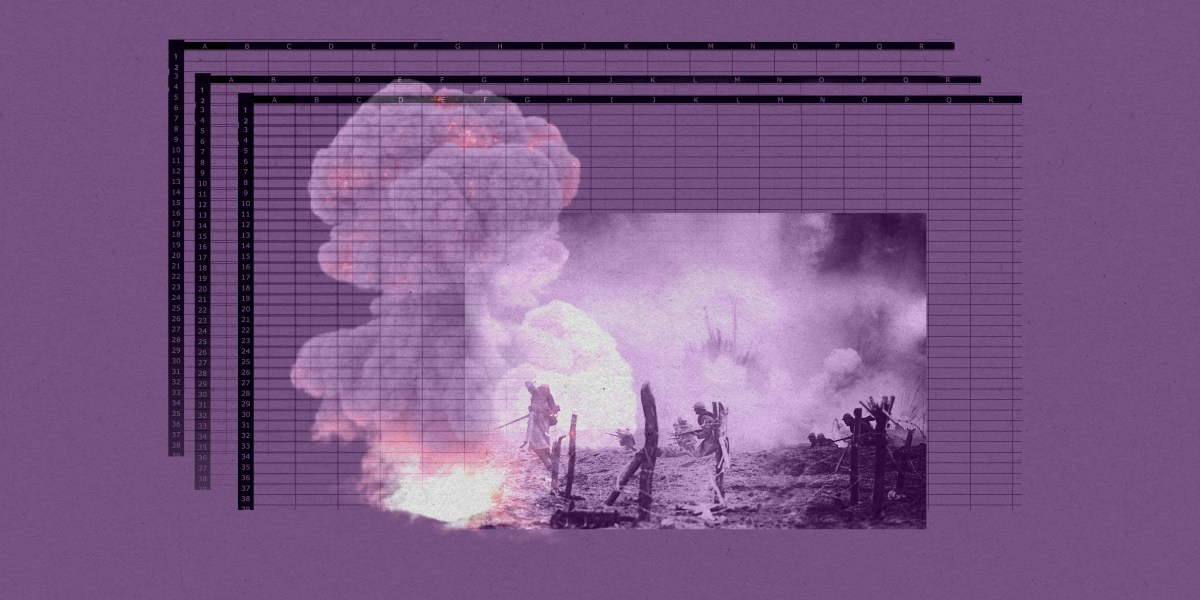

Arthur Holland Michel does a great job looking at the complicated and nuanced ethical questions around warfare and the military’s increasing use of artificial-intelligence tools. There are myriad ways AI could fail catastrophically or be abused in conflict situations, and there don’t seem to be any real rules constraining it yet. Holland Michel’s story illustrates how little there is to hold people accountable when things go wrong.

Last year I wrote about how the war in Ukraine kick-started a new boom in business for defense AI startups. The latest hype cycle has only added to that, as companies—and now the military too—race to embed generative AI in products and services.

Earlier this month, the US Department of Defense announced it is setting up a Generative AI Task Force, aimed at “analyzing and integrating” AI tools such as large language models across the department.

The department sees tons of potential to “improve intelligence, operational planning, and administrative and business processes.”

But Holland Michel’s story highlights why the first two use cases might be a bad idea. Generative AI tools, such as language models, are glitchy and unpredictable, and they make things up. They also have massive security vulnerabilities, privacy problems, and deeply ingrained biases.

Applying these technologies in high-stakes settings could lead to deadly accidents where it’s unclear who or what should be held responsible, or even why the problem occurred. Everyone agrees that humans should make the final call, but that is made harder by technology that acts unpredictably, especially in fast-moving conflict situations.

Some worry that the people lowest on the hierarchy will pay the highest price when things go wrong: “In the event of an accident—regardless of whether the human was wrong, the computer was wrong, or they were wrong together—the person who made the ‘decision’ will absorb the blame and protect everyone else along the chain of command from the full impact of accountability,” Holland Michel writes.

The only ones who seem likely to face no consequences when AI fails in war are the companies supplying the technology.

It helps companies when the rules the US has set to govern AI in warfare are mere recommendations, not laws. That makes it really hard to hold anyone accountable. Even the AI Act, the EU’s sweeping upcoming regulation for high-risk AI systems, exempts military uses, which arguably are the highest-risk applications of them all.

While everyone is looking for exciting new uses for generative AI, I personally can’t wait for it to become boring.

Amid early signs that people are starting to lose interest in the technology, companies might find that these sorts of tools are better suited for mundane, low-risk applications than solving humanity’s biggest problems.

Applying AI in, for example, productivity software such as Excel, email, or word processing might not be the sexiest idea, but compared to warfare it’s a relatively low-stakes application, and simple enough to have the potential to actually work as advertised. It could help us do the tedious bits of our jobs faster and better.

Boring AI is unlikely to break as easily and, most important, won’t kill anyone. Hopefully, soon we’ll forget we’re interacting with AI at all. (It wasn’t that long ago when machine translation was an exciting new thing in AI. Now most people don’t even think about its role in powering Google Translate.)

That’s why I’m more confident that organizations like the DoD will find success applying generative AI in administrative and business processes.

Boring AI is not morally complex. It’s not magic. But it works.

Deeper Learning

AI isn’t great at decoding human emotions. So why are regulators targeting the tech?

Amid all the chatter about ChatGPT, artificial general intelligence, and the prospect of robots taking people’s jobs, regulators in the EU and the US have been ramping up warnings against AI and emotion recognition. Emotion recognition is the attempt to identify a person’s feelings or state of mind using AI analysis of video, facial images, or audio recordings.

But why is this a top concern? Western regulators are particularly concerned about China’s use of the technology, and its potential to enable social control. And there’s also evidence that it simply does not work properly. Tate Ryan-Mosley dissected the thorny questions around the technology in last week’s edition of The Technocrat, our weekly newsletter on tech policy.

Bits and Bytes

Meta is preparing to launch free code-generating software

A version of its new LLaMA 2 language model that is able to generate programming code will pose a stiff challenge to similar proprietary code-generating programs from rivals such as OpenAI, Microsoft, and Google. The open-source program is called Code Llama, and its launch is imminent, according to The Information. (The Information)

OpenAI is testing GPT-4 for content moderation

Using the language model to moderate online content could really help alleviate the mental toll content moderation takes on humans. OpenAI says it’s seen some promising first results, although the tech does not outperform highly trained humans. A lot of big, open questions remain, such as whether the tool can be attuned to different cultures and pick up context and nuance. (OpenAI)

Google is working on an AI assistant that offers life advice

The generative AI tools could function as a life coach, offering up ideas, planning instructions, and tutoring tips. (The New York Times)

Two tech luminaries have quit their jobs to build AI systems inspired by bees

Sakana, a new AI research lab, draws inspiration from the animal kingdom. Founded by two prominent industry researchers and former Googlers, the company plans to make multiple smaller AI models that work together, the idea being that a “swarm” of programs could be as powerful as a single large AI model. (Bloomberg)