Fashion

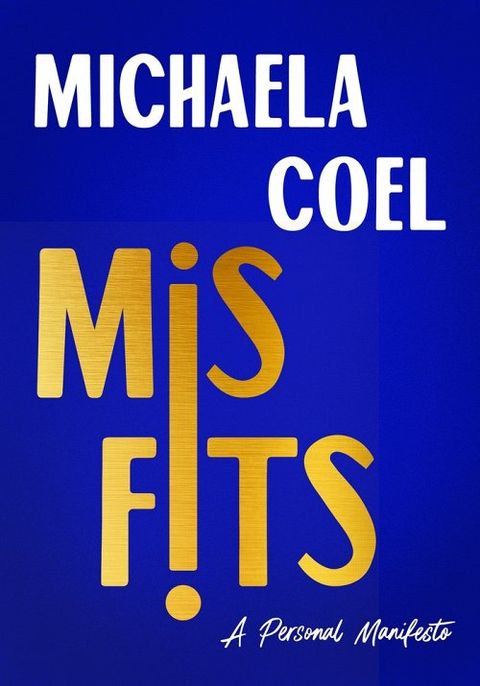

How Michaela Coel Found Her Voice

Published

4 years agoon

By

Terry Power

I was born and raised in London. The Square Mile, sometimes considered Tower Hamlets, sometimes considered “City of London”; home to both the Stock Exchange and the Bank of England.

Between its modern corporate skyscraper towers and medieval alleyways exists a social housing estate. Right there, in plain sight, yet somehow unseen. It was originally built in 1977, with the aim to help homeless people in London, and that’s my proud home. Even now, there may be someone rushing past it for the hundredth time, briefcase in hand, with no idea this council estate exists.

We lived directly opposite the Royal Bank of Scotland, which somehow felt “other” and slightly bizarre. Not the Scottish bit, the Royal Bank bit.

It was clear I liked telling stories. I was told to apply for something called a drama school, so I dropped out of uni, again. It was my second go at it, and in two years I’d been to only one English lecture. The lecture was fine, was good, but I bumped into a friend on the way out and found out I’d just sat through a lecture for law students. I’d no idea. I’d even taken notes. So I left, to “tell stories.” My mum was concerned; she was an NHS mental health nurse at the time, and what could she do but watch my future fall into uncertainty? Where was I climbing to? Why was there no clear sign of safety at the end of the ladder?

I got in, to a drama school. In a year of only twenty-three. A drama school in my Square Mile; I’d grown up walking past it my whole life not knowing what it was, and now I was a member of its family. I was told its theatre attracted agents from far and wide, and during the final year they’d come to see us perform and sign the hottest talent. Like kids scrabbling for a sweet from above. Silk Street Theatre—where the hottest talent met the hottest agents, to partner with the hottest casting directors, to make the hottest period dramas.

I was the first Black girl they’d accepted in five years, a fact which the head of the school described to me as “the elephant in the room.” This was my third attempt at a university. I’d still never been into a pub, to a festival. I just hadn’t. I’d never watched Fawlty Towers or Red Dwarf or heard of any festival in Edinburgh, I just hadn’t, and struggled to converse on things I didn’t know about. I was watching a lot of TV—Seinfeld, Moesha, The Golden Girls, Buffy—shows no one really spoke about. So, I spent most of my time perched in the corridor, hoodie up.

I wrote about the resilience born from having no safety net at all, having to climb ladders with no stable ground beneath you.

I was called a nigger twice in drama school. The first was by a teacher during a “walk in the space” improvisation that had nothing to do with race. “Oi, nigger, what you got for me?” We students continued walking in the space, the two Black boys and I glancing at each other whenever we passed . . . “Who’s she talking to?” we’d whisper, “Boy, not me,” “Nah, that was for you,” passing around responsibility like a hot potato, muffling our laugh-snorts. I wonder what the other students thought of our complicity. The second time was a girl in my own year. After class, the same two boys and I found ourselves perched in the corridor; she passed and waved. “See you later, niggers!” . . . We three Blacks of Orient were posed with a dilemma—“niggers” . . . plural. This hot potato belonged to us all. I chose to act. I called her back and calmly gave her sound advice. She smiled, continued her way and never said sorry.

Drama school was problematic in so many ways. As an Evangelical Christian, the plan was to teach the homosexuals about Jesus, but I accidentally ended up becoming best friends with some and learning from these other kind of misfits. Yes, homosexual bonds replaced biblical ones. I still love the character of Jesus. I just started paying attention to the stuff written around Him, and didn’t care for what I read.

We were told at school, if we wanted to pursue this, we should be “yes” people, and expect to be poor for the rest of our lives. “Climb because you want to tell stories.” I loved the concept! All of us united, climbing toward storytelling at the risk of poverty, screaming “Yes!”

In a class exercise, however, the teacher commanded we run to point A if our parents owned a home or to point B if they didn’t. When everybody else ran to point A, and I found myself isolated at point B, I was astounded. Had land-owning taken over my race? Why did this class exercise even exist? I thought, then blogged about it. Not about how hard it was not owning a house; I wrote about the resilience born from having no safety net at all, having to climb ladders with no stable ground beneath you.

On top of it, all our ladders were faulty, born climbing a ladder before we could walk, and better climb fast lest it snap beneath your feet! I told people to keep climbing, for the love of it, whatever the craft, not because of financial profit, or safety. What is “safety”? I wrote that such circumstances can leave you feeling destined for defeat, or it could do something else; it could breed a determination, a relentless pursuit of one’s dreams that no safe man could ever replicate. I changed the narrative, twisting it in my favor.

This idea of a profit ladder was producing such a desperate pursuit in some around me. For those who had no means of getting more—they were arrested. I was aware, even then, that the proportion of Black people imprisoned in the UK was almost seven times our share of the population.

I loved the concept! All of us united, climbing toward storytelling at the risk of poverty, screaming “Yes!”

I blogged again.

One day an emergency meeting was scheduled between our year and the teachers. We gathered. Some students made small talk about the toilets not flushing, a teacher assured they’d be fixed, then BANG. “Michaela, what are these blogs?”

I’d upset people, people who didn’t see color or class. A year later, a friend saw me perched in the corridor. She apologized for going to the teachers back then and orchestrating a meeting that she and many others knew would take place long before it occurred. I also knew that already, because a homosexual gave me a tip-off in advance: tribe.

I just loved the craft. I didn’t mind the occasional “nigger” slip or military coup; I just wanted to be a lead on the Silk Street stage, I had to get a lead part at least once. I’m the first Black girl in half a decade! How could they not? My ego’s dreams came true. I was to play a role so important it was the name of the play— Lysistrata in Lysistrata—and my year were really happy for me. We only later found out this performance wouldn’t be on Silk Street; it would be in South London, a thirty-five-minute drive across the river. My mates were sad. They hugged me. “No agent is going to come to this, Michaela, not the hot ones. They simply won’t cross the river.”

I lived in E1; everyone who lives in E1 knows: we live by the river, but even we don’t cross it.

There was also the option to remove yourself from a main show to do a fifteen-minute solo piece; rarely did anyone do this as it wasn’t on Silk Street, it was in the basement floor of the theatre.

Misfits: A Personal Manifesto

But this wasn’t about agents anymore; it was a chance to create something that wasn’t a period drama designed in period costumes. I wanted to make something for this period, so I did both. I wrote a dark comedy called Chewing Gum Dreams. A title born from a poem; that poem born from an image in my mind. Of a tall council flat, tall as the Tower of Babel, winged falcons soaring round its highest floor in perpetual circles. Watching the jet planes and helicopters fly by, curious of life beyond their tower, but terrified of leaving it. Their wings were weighed down by gossip, dissemination, rivalry, fitting in, but also by love, passion, dreams. There’s only so much a falcon could carry, so we’d offload the things society taught us were most superfluous: dreams, love and passion, and down they’d descend. Dreams, free-falling from our tower block, already forgotten before crashing into the pavement, trampled on by our newly acquired designer trainers, squashed into the pavement like chewing gum: Chewing Gum Dreams. I played eleven parts. The response in that basement was something neither I nor they had ever experienced, and on that high I did what I do best: I dropped out.

Excerpted from Misfits: A Personal Manifesto by Michaela Coel. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2021 by Michaela Coel. All rights reserved.

Michaela Coel is the creator of the hit TV shows Chewing Gum and I May Destroy You and a BAFTA, Royal Television Society, Broadcasting Press Guild, and NAACP prize–winning actor, screenwriter, and director, who was included in Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People and British Vogue’s 2020 Most Influential Women lists in 2020.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

You may like

-

The Download: unlocking Chinese social accounts, and AI voice analysis

-

Suicides Linked To This Common Food Preservative Are Increasing; Experts Voice Concerns

-

The Download: Retrofitting cities, and Alexa mimics the dead

-

Podcast: How AI is giving a woman back her voice

-

Ortovox Diract Voice Avalanche Transceiver Is a Mountaineering Must

-

Ariana Grande Dressed Up Like Jenna Rink in Her ‘13 Going on 30’ Versace Dress for ‘The Voice’

Fashion

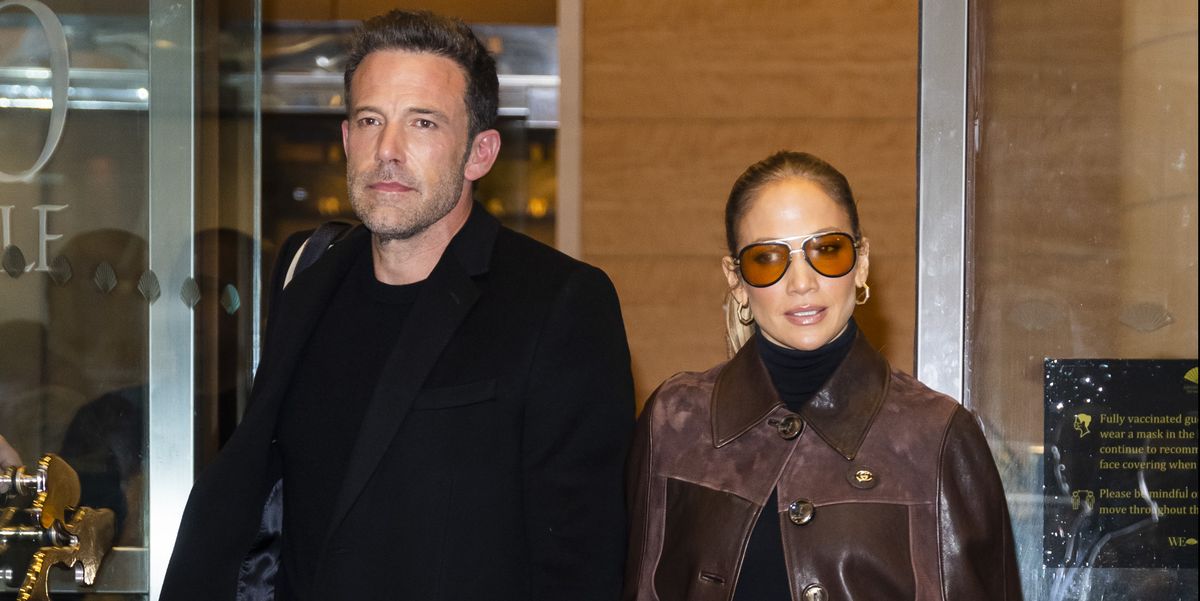

Jennifer Lopez Joined Ben Affleck In L.A. With Kids For Thanksgiving

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

On Wednesday night, Jennifer Lopez arrived in Los Angeles with her 13-year-old twins Max and Emme. The family was likely there to join Lopez’s boyfriend, Ben Affleck, for the Thanksgiving holiday. Lopez recently returned from the much colder climate of British Columbia, Canada, where she was filming her latest project, The Mother.

J. Lo touched down in her private jet wearing a teddy fur coat from Coach’s Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, and a pair of Ugg boots. Classic airplane outfit, celebrity style. Lopez and Affleck originally dated in 2002 and broke up in 2004. Their romance was rekindled earlier this year, soon after Lopez ended her relationship with baseball player Alex Rodriguez. The new couple went official in July, while celebrating Lopez’s 52nd birthday abroad.

Affleck’s most recent relationship with Ana de Armas ended in January after about a year together. He had divorced ex-wife Jennifer Garner in 2015 after being married for almost a decade. Garner and Affleck had three daughters, Violet, Seraphina, and Sam.

Before traveling back to the U.S., Lopez posted a story to Instagram Reels about how grateful she was to be headed home.

“Hey everybody, it’s my last day here shooting on The Mother out in Smithers in the snow, it’s been beautiful, but tonight I’m on my way home,” she said, as she walked through the wild landscape in a black coat and beanie.

“I’m so excited for Thanksgiving! I hope everybody has an amazing weekend with their families and their loved ones, there’s so much to be grateful for this year. I’m on my way!”

This is the first major holiday of the year since Lopez and Affleck reunited, so it’s likely to be a big one for both families.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Fashion

Everlane’s Black Friday Sale is Packed With Winter Essentials

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

Courtesy

This is not a drill: Everlane just kicked off its Black Friday sale. Now through Monday, November 29, the direct-to-consumer brand is offering 20 to 40% off its cozy sweaters, minimalist activewear, and popular jeans. If you’re not super familiar with Everlane, let me spell it out for you: this is a big deal.

The e-tailer might be known for making sustainable, ethically made clothes and accessories at a fair, affordable price, but Everlane rarely has sales beyond its Choose What You Pay section. So, if you want to stock up on cute basics for less, now’s your time to shop.

And, in true Everlane fashion, the brand is taking this opportunity to give back. Everlane is partnering with Rodale Institute and help U.S. farmers transition their farmland to regenerative organic—and donating $15 per order to the cause. A great sale that gives back? I’m sold.

But, hurry! These deals are going to sell out fast, so you won’t want to waste any time filling your e-cart.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

1

The Cloud Turtleneck

$150 $105 (30% off)

Sweater weather is officially here, so why not pick up a few fresh layers? This turtleneck is the S’s: snuggly, stylish, and on sale.

2

The Authentic Stretch High-Rise Skinny Jeans

everlane

$78 $58 (25% off)

Looking for a great pair of jeans, minus the markup? Everlane’s classic skinny style is not only super stretchy, but it’ll look good with everything from chunky sweaters to silky blouses.

3

The ReNew Teddy Slippers

everlane

$65 $39 (40% off)

Why limit the shearling trend to the upper half of your body? These plush slippers will give even your most worn-in sweats a stylish edge.

4

The Chunky Cardigan

everlane

$110 $77 (30% off)

Sure, this may not be the cardigan Taylor Swift was talking about. But, with an exaggerated collar and ribbed finish, this style would definitely score top marks from the singer herself.

5

The Canvas Utility Boots

everlane

$115 $59 (40% off)

Brave the cold weather in style with Everlane’s chic boots. The canvas uppers and thick sole make these an ideal, all-weather option.

6

The Lofty-Knit Henley

everlane

$150 $105 (30% off)

Made with a nubby blend of merino wool, alpaca, and recycled nylon, this henley is perfect for a cozy night in, yet stylish enough to wear in public.

7

The Perform Bike Shorts

everlane

$45 $22 (51% off)

No, you can never have too many stretchy pants. Everlane’s bike shorts ooze major Lady Di vibes — for under $25, no less.

8

The ReLeather Court Sneakers

everlane

$110 $66 (40% off)

Made with recycled leather, these refresh sneakers will serve up major curb appeal — and Mother Nature’s seal of approval.

9

The Field Dress

everlane

$100 $60 (40% off)

Found: a fun, flouncy frock you can wear year-round. For a wintry take, pair with opaque tights and your favorite chunky boots.

10

The Cozy-Stretch Wide-Leg Sweatpants

everlane

$150 $75 (50% off)

With a straight-legged silhouette and wool material, it’s safe to say these are the chicest sweatpants we’ve ever seen. To sweeten an already enticing offer, this pair is half off.

11

The Organic Cotton Flannel Popover

$80 $56 (30% off)

Everlane reimagined the traditional flannel with a cropped silhouette, voluminous sleeves, and a slew of minimalist colors.

12

The Studio Bag

everlane

$275 $192 (30% off)

Large enough to fit all your essentials, but not too big that it’ll weigh you down, Everlane’s Studio Bag is the perfect everyday purse.

13

The ReNew Long Liner

everlane

$158 $118 (25% off)

House Stark was right: winter really is coming. Made with recycled materials, this liner is a great layering piece that’s considerably chicer than the yesteryear’s Michelin Man-worthy parkas.

14

The Felted Merino Beanie

everlane

$50 $30 (40% off)

All set on clothes? Pick up this cheery beanie, which is 40% off its original price.

Kelsey Mulvey is a freelance lifestyle journalist, who covers shopping and deals for Marie Claire, Women’s Health, and Men’s Health, among others.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Fashion

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy

Published

3 years agoon

26 November 2021By

Terry Power

29 Winter Fragrances That Exude Main Character Energy